Small Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in New Zealand – A roadmap for SME owners to grow and eventually exit their companies

By Allan Rodrigues

Introduction

There is a common belief in New Zealand that a Kiwi with a cell phone, a ladder and a van is a limited liability company waiting to happen.

Walk into any growing SME and you see an unmistakable pattern of ownership and management that is truly Kiwi. One partner acts as the fox, spending all of his or her time finding opportunities in the marketplace. The other partner acts as the hound. His or her primary task is to keep a weather eye on the fox (often unsuccessfully), while trying hard to organise ‘the pack’ into some semblance of order to (hopefully), catch up with the fox.

The hound (like all long suffering hounds) never seems to be able to hold the fox in its line of sight for as long as it would like. Meanwhile, the fox blithely forges on secure in the universal belief of all foxes that, “She’ll be right mate”.

Despite this state of affairs, many SMEs are very successful at what they do and grow rapidly because they are fleet of foot. They instinctively know that a combination of constant innovation and a robust customer focus are the keys to success in a marketplace where demographics are low and competition is fierce.

In theory this level of successful entrepreneurship should make New Zealand the leading incubator of small businesses.

The reality is that most SMEs in New Zealand do not survive their original owners, rarely create shareholder value of significance (other than their salaries), and more often than not are sold for less than their potential by their owners when they reach the end of their working lives.

On the other hand a select few businesses thrive and grow into spectacularly large behemoths, or are very successful at whatever size they are. This begs the question…

“Why are some small (often family owned) businesses able to manage the transition into becoming large behemoths, or are able to transfer wealth to a new generation of owners (inside or outside the original family), whilst others are not?”

The answer it appears lies more within the SME itself and in the ability (or inability) of many SME owners to recognise crucial moments in the life of their businesses when the need for major (often traumatic) change becomes ‘mission critical’.

Growing SMEs are usually family businesses that begin with a product or service innovation that captures the imagination of the market. They grow rapidly along a ‘hockey stick curve’ that in turn drives a heavy demand for all types of resources, e.g. finance, people and management time.

SMEs rarely bother with their balance sheets. They live or die by their Profit and Loss Accounts.

For a vast majority of SMEs the balance sheet is something the accountants bring to a boil every once in a while. They assume that if the balance sheet ‘balances’ it has done its job (whatever that might be). It is then consigned to the bottom drawer where it never sees the light of day.

To add to the confusion it doesn’t help that the balance sheet is called the Statement of Financial Position (SFP) in the Financial Reporting Act. At least the old name told you (if nothing else) that something was supposed to balance.

Two questions immediately spring to mind…

- Firstly, “Why do good accountants give so much importance to whether the business has a strong or a weak balance sheet?”

- Secondly, “How do really astute businesspeople use their balance sheet as a formidable weapon in the marketplace?”

For most other companies the annual balance sheet (sorry SFP) is largely a nuisance that is ignored, or at best looked at in passing with little in the way of understanding what to look out for.

Not surprisingly these firms end up with a high gearing (debt to equity ratio). The bank manager quickly recognises that this increase in debt is far too risky for the bank, and in turn demands an increasing amount of personal security as collateral, since the firm itself in many cases has no assets, equity or retained earnings to speak of.

Owner managers resent this bitterly but are powerless in the face of an increasing demand for their products that must be supported with finance and other resources.

The bank manager rarely understands the innards of the firm’s business plan (if it even has one), and is forced to rely on a hierarchy of key business ratios based on past performance rather than future strategy. Not surprisingly, they often misunderstand the business model.

The Roadmap followed by successful SMEs

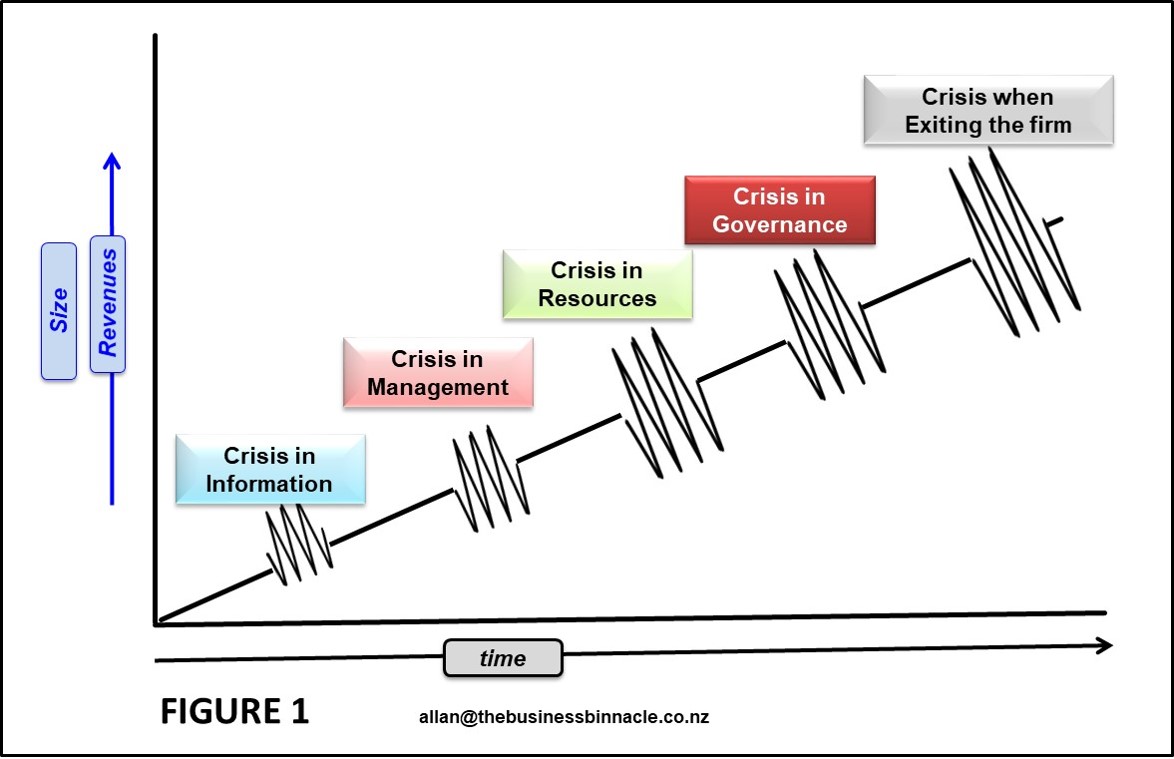

There are 5 key crisis points that occur in the lifecycle of any SME (see Figure 1 below)…

- Crisis in Information (the need for critical information at key moments)

- Crisis in Management (some skill sets are beyond the founders’ experience)

- Crisis in Resources (the ability to attract finance and other critical resources)

- Crisis in Governance (managing shareholder value and wealth)

- Crisis when Exiting the firm (succession plan and a fair value on exit)

1. Managing the Crisis in Information – Positioning for Advantage

In this age of technology SMEs (however small) rarely face a crisis in information in the early stages of the lifecycle of the firm. The use of computers is almost second nature. There are fairly robust entry-level information technology-driven business and accounting systems that proliferate in the market.

As these SMEs grow over time, however, their information needs increase dramatically, in turn requiring skills at collating and analysing large (often vast) amounts of data to support intelligent decision making.

Many firms at this stage do not realise they should be information led and not technology led in the search for a good package that suits their needs. The focus should be on collating and using information intelligently, and not on the bells and whistles that a particular software package can provide.

Eventually most growing SMEs find an ERP system (often the second time around) that addresses many of their needs. The crisis in information (for the most part) at the IT level is an easy fix that SMEs manage well in the main.

There is a second crisis that brews almost concurrently centred around using information to position the company to advantage.

At some stage SMEs sign on to the concept of the ‘annual budget rain dance’. The focus is on annual ‘incremental increases’ of small achievable growth targets.

Successful SMEs, on the other hand, take a different route. They look at the lifecycle of their products/services instead.

New products that are early in their lifecycle (new innovations, or early market entrants) take the market-based view, i.e.

- “How much can we grow this product by?” and

- “How can we source funds to support revenue growth without breaking our backs?”

Grabbing market share becomes the name of the game. Consequently the firm’s ability to attract financial resources at the right time makes all the difference.

Products that are mature usually have many suppliers. Revenue growth is limited by the many players who vie for the same share of the pie. Average SMEs focus on incremental growth (if at all) and stick to this annual budget/variance rain dance every year, driven by information extracted from their accounting systems. They neither grow (significantly) nor shrink.

For many SMEs this approach is perfectly acceptable as it does provide a tidy income to the owners.

Ambitious SMEs, however, tend to shake up the status quo. Their budgets are not based on tired increments of a few percentage points each year.

They keep their eye on the competition and benchmark their performance in any year based on what the competition is doing (or seeking to do), rather than some arbitrary budget target. The aim is to cede nothing to competition.

Moving from ‘Value Propositions’ to ‘Competitive Advantage’

Apex SMEs add on another gear to their growth engine. They understand that a revenue and cost budget by itself tells a small part of the story. The real story is in how an SME can fund its growth and fight effectively for its share of revenue.

This is where good SMEs transform themselves to move away from a narrow focus on ‘annual revenue-increase budgets’ based on selling their Value Propositions (the value they add to their customers or suppliers). They focus instead on Competitive Advantage (the reason their customers prefer their product/service offerings over every other competitor).

This is a subtle difference in positioning that is often missed. It is competitive advantage that creates sustainability in revenue growth and in the cash flows that these revenues generate. It is the customers who make the choice to stay and even market the services of the SME by staying loyal.

The key elements of competitive advantage that drive their business models are…

- Product leadership for customers who are early market entrants.

- Customer intimacy by getting to know their customers who in turn stay on for the long haul.

- Operational efficiency based on value pricing and the ability to ‘deliver in full and on time’.

- System lock-in in product design itself or in service delivery (financiers love lock-in strategies).

- Long-term retention of key skill sets (rather than a narrow focus on any particular staff member).

Good SMEs position themselves to exploit these key elements of competitive advantage. Their budgets focus on growth as well as the resources needed to fund growth. A focus on competitive advantage allows these SMEs to grab large chunks of market share at opportune moments. This approach is far more effective than a narrow focus on small incremental annual budgets.

2. The Crisis in Management

Growth if managed well provides superior returns. If not, it produces pressure points across the business process.

Managing capacity, scheduling, inventory and the optimisation of their global supply chains needs very fine judgement calls that are often outside the experience of most owner managers. High levels of inexperience amongst both management and staff results in crucial errors that are the cause of customer unhappiness, low morale and a loss in value.

Owner-managers wear two hats – a management hat and an ownership hat. The management hat is well understood and driven from the P & L for the most part. Managers need to be able to provide their owners (often themselves) with a good return on the operating assets of the company.

Owners, on the other hand, measure the return on the money they have invested and how the return increases the value of the company. Money left behind in the company (called capital employed) consists primarily of Equity (and Debt). In addition they realise that they have also invested (often at zero return) in high inventory and/or their shareholders current accounts.

Successful SMEs understand what needs to be done. The owner continues as the fox of the company but appoints a professional hound to manage the business.

Owners who prefer managers who are mirror images of themselves fail to address many of the problems that arise along the way. When that happens many of these companies muddle their way into mediocrity or oblivion.

Eventually the good companies get it right. They find the right manager who has the right industry and market nous and the right understanding of how a business must create wealth for its shareholders.

Delegating the management of operations to a line manager requires the SME owner to have a good understanding of their balance sheet, as The P & L does not capture the whole story. The underlying principles of how assets and liabilities create wealth are key elements in this mix.

Understanding the business model, the operational decisions made, liquidity, capital structure optimisation (Debt versus Equity), solvency and desired return are skill sets that must be mastered. Key results must be monitored against a scorecard (however rudimentary). Budget targets need to be driven not just by profitability and efficiency but by wealth generation.

Many companies up to this point usually continue operating with a governing director to avoid overcomplicating the business model. At some stage realisation sets in that governance through a board of directors might be advantageous, particularly if the providers of funding are from outside the immediate family of owners.

3. The Crisis in Resources

Many SMEs that have been in business for generations are often set in their ways, particularly if they have operated for years in small markets where their standing is very good.

Marketplaces eventually change. When they do, these changes are sudden, traumatic, and often because of changes in customer expectations (driven by information freely available on the web) or changes in technology, demographics or market dynamics.

Companies that hitherto had a monopoly in a particular product/service segment (or distribution), find themselves fighting competitors who appear seemingly and without warning from over their horizon, often courtesy of the internet.

There is an initial inertia to change that is innate amongst many SMEs. Their acutely honed early warning radars fail at times.

Conversely some SMEs thrive in the hurly burly of change and grow at a great rate of knots. This growth becomes an engine that demands resources that are far more than the company’s shareholders can provide. The SME at this point faces a resource crisis brought on by growth. They need high inventories to support growth, often creating a desperate and growing need for working capital.

Many SMEs borrow heavily from the bank. In a few unfortunate cases, timing issues in their cash flows cause a short fall. Eventually the demands for cash become extreme, resulting in the unthinkable where they lose their company and, in many cases, their personal assets which they offered up as collateral along the way.

The road to success in the marketplace is littered with the corpses of very successful companies that ran out of cash at critical junctures.

This is the crisis in resources. When it occurs it must be intelligently managed. Smart SMEs understand how to attract funding at these critical moments by attracting investments from imaginative debt/equity funders who provide the best risk versus return trade-off.

Assuming there is no downturn (in the company’s fortunes, or the economy), many of these SMEs will either grow or stay static. The static SMEs will continue operating as before, secure in the knowledge that ‘she’ll be right mate’ until change comes upon them.

This ‘do nothing unless you are forced to do something’ attitude is actually prudent and often successful. It works provided these SMEs are able to anticipate and deal with change (or competition) when it does eventually come upon them.

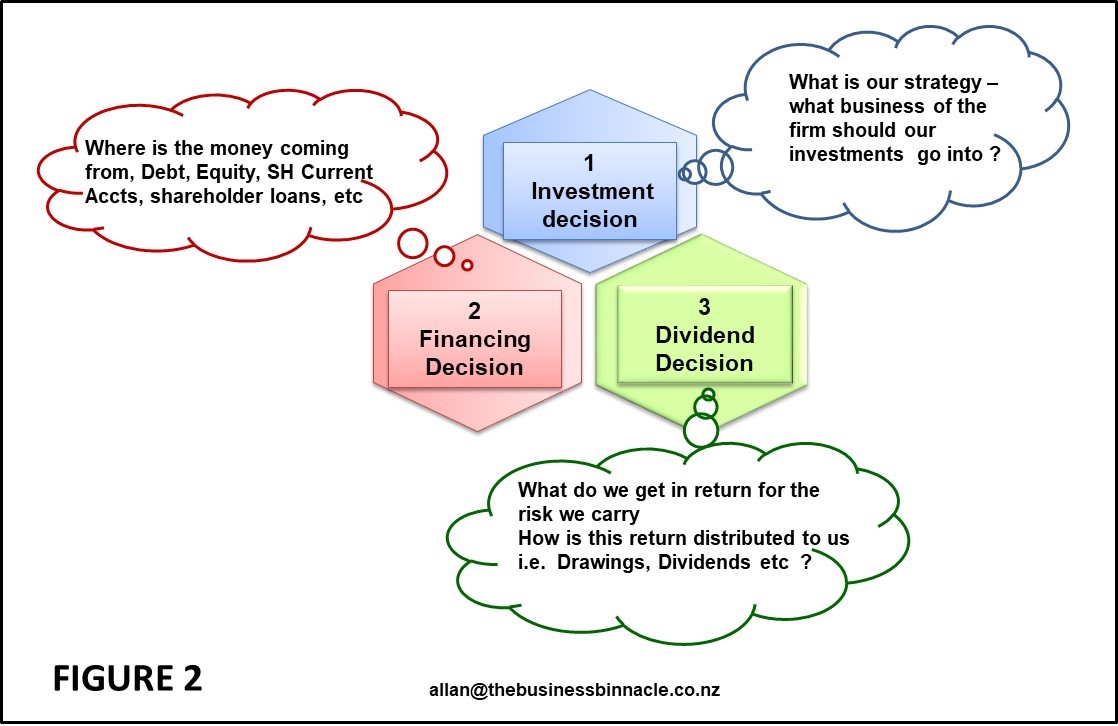

There are three key decisions that drive success at this level that have been captured in a self-explanatory diagram at Figure 2 shown below:

A key point that is often missed is that SMEs never have a debt in the truest sense of the word. Debt is not the cheap source of funding they think it is when the loan is secured against the family home as collateral (even if the mortgage interest rate is low).

Debt in these circumstances is as risky as equity. If these SMEs default on their debt they lose their homes.

This is not debt, but a form of high-risk equity funding that converts the family home into cash for a period of time. It is very risky and should be used only if the strategy envisaged is able to provide a return on investment that is commensurate with this high risk.

Raising debt is no longer based on the comfort zone of the SME owner. Raising debt or equity becomes a strategic decision.

Value driven companies tend to drive up debt during high growth periods but retain the ability to retire their debt when growth begins to plateau, or when the company begins regrouping before the next growth cycle.

The debt trap can be avoided if there is visibility in the business model. Visibility makes it easier to attract outside equity shareholders or even angel investors who often prefer Preference Shares that pay fixed dividends with the flexibility of being accruable from one financial year to another if required.

There are a number of financial instruments that are preferred by angel funders/low-end bootstrap funders that are less risky than debt secured by the family home. However, none of them will fund an SME unless there is clear visibility in how value is created, captured and distributed to the investors. This is a critical insight that is often missed.

An uncomplicated simple-to-use scorecard that focuses on both financial and non-financial measures relating to the firm’s Critical Success Factors and Critical Limiting Factors should be used to capture performance.

This scorecard (a balanced scorecard is a case in point) should capture the impact of the firm’s financial returns, internal business processes, customer performance, supplier measures and other key stakeholder parameters.

A closed learning loop that monitors performance and uses the feedback to drive future strategies/objectives provides both the visibility and motivation for investors to invest.

4. Addressing the Crisis in Governance

SMEs that have internalised lessons from the issues around resource management tend to grow very rapidly. By this time their original owners are often apex managers (Managing Directors), whilst professional line managers manage operations at the coal face.

A key requirement for any SME delegating authority to a management team is the need to understand the whole story surrounding the company’s business model. This bit is often neglected.

Risk versus Return (wealth creation)

SMEs must have a good understanding of the risks underlying the company’s strategy and on what constitutes a commensurate return that is acceptable.

An easy way of benchmarking the risk is to look at equivalent risky and/or less risky opportunity costs available to the shareholders.

As the company grows, more formal methods of establishing a fair return based on the unique risks of the SME can be undertaken by obtaining professional advice on the cost of capital (or cost of finance).

A number of easy to use methods are available that SME boards should be able to employ without overcomplicating the issues involved. Some of these are captured in the section on Exiting a Company below.

The need for governance from a board of directors

If it has not happened already, this is the moment for the SME to appoint a small steering group (often 3 or 4 people) as directors on a formal board. Introducing a layer of corporate governance is essential if the resources obtained from disparate funding agencies and from different classes of shareholders are to be managed well.

More often than not SMEs are unfamiliar with how a board should operate. As a consequence SME boards often tend to devolve into a layer of bureaucracy that stifles creativity and hinders efficiency. When this happens the whole concept of governance through a board is abandoned as unworkable.

Conversely good SMEs obtain the services of an independent director (non-shareholding), at least during these formative stages, so that they are able to understand how good governance can actually add value in the short and long term.

An independent director is a good fit for growing companies (even in family owned ones) to ensure the board is given feedback from an independent source. Care should be taken to ensure these directors are not over employed otherwise their costs can become prohibitive.

A Dividend Policy

Having a proper dividend policy is critical. Often there is some confusion on what constitutes a dividend.

A dividend is actually a return, and in finance parlance it is part of the Free Cash Flows (or cash freely available to the shareholders) after the working capital and growth needs of the business are met. (See the section below on Exiting a Company).

SME owner managers tend to find innovative (and perfectly legal) ways of extracting value and wealth for themselves. In smaller companies profits earned are arbitrarily reduced by arbitrarily increasing owner salaries, which are then transferred to the Shareholder Current Accounts in the Current Liabilities section of the balance sheet. Shareholders take drawings as and when cash is available from here.

The risk to the shareholder is perceived to have been reduced, as the Limited Liability provisions confine the liability of the shareholder to the equity of the firm, which is minimal. In this methodology there is very little profit (if at all) that is transferred to the retained earnings to grow the equity of the company.

This is a standard operating procedure for small SME owners who run their companies solely for the purpose of creating wealth for themselves. Taking the money out to create personal assets/wealth makes eminent sense when the company is small and the brand and goodwill are linked directly (often personally) to the shareholder. There are tax benefits that can be exploited depending on the specific circumstances of each case.

Conversely such a dividend strategy, if one can call it that, actually increases the risk profile of the company. SMEs with no equity to speak of and no visibility in their business models tend to be undervalued.

A marked preference for keeping one’s investments easily liquid (as current accounts tend to be) also signals that the firm has fears about its longevity.

Whilst this might not be true (and probably isn’t in most cases), it does beg the question as to why a successful, growing, medium-sized SME would avoid retaining its earnings as equity. Considering that New Zealand has imputation credits the tax impact would not be seen as severe.

Good SMEs understand this. As the firm begins to grow, the board begins to weigh up the pros and cons of:

- Opting for the tax and liquidity advantages of having profits captured as Shareholders Current Accounts, or

- Retaining all or a part of their profits as retained earnings from which dividends are paid out after utilising all available imputation credits.

It should be mentioned that investors prefer constant regular dividends instead of sporadic large payouts. Constant steady dividends are seen as an indication of prudent money management. Steady dividend policies allow both the firm and its funders a measure of security.

In any case, nothing whatsoever stops the firm from paying out additional dividends as and when there are super profits to be distributed.

Shareholder Agreements

A proper shareholders agreement should have been put into place fairly early in the life of the firm. If this has not been done, it needs to be addressed as soon as possible by the board.

A number of SMEs use a standard boilerplate agreement obtained from the internet or from sources freely available. Many of these are actually well written.

No two companies are alike however, even if they operate in the same industry and follow the same operating principles. It is important that these agreements are customised to the circumstances of the company.

How the business model uses its funds and manages its assets, liabilities, capital structure, and how any dividends (or drawings) are distributed to owner shareholders can differ widely between similar companies. The shareholders themselves may well be part of the same family trust but with different motivations and expectations, or be a combination of different individuals and trusts sharing ownership.

There is also the issue of shareholders leaving the firm, which can be a fairly complex event in reality. Shareholders leave under a variety of circumstances forcing the SME to acquire their shares for reasons such as…

- Disciplinary reasons, where a shareholder (or shareholding director) has breached the terms of the agreement.

- Voluntary exit to pursue opportunities elsewhere.

- The unfortunate death/incapacitation or even advancing age of a shareholder that may require his or her shares to be acquired.

Each of these situations present a different risk to the remaining shareholders who are staying back. Even the death of a shareholder can be a complex event if the beneficiaries of the trust (often family partners, extended family, etc) who have no direct interest or attachment to the SME choose to be difficult.

Planning for the exit of a shareholder is a critical requirement for any successful SME with a reasonably large portfolio of assets.

It is useful for SME owners to undergo some basic training in corporate governance. A number of institutions in New Zealand offer support in this area. Convenient short courses are offered by the Institute of Directors. In addition a number of universities and their affiliates offer short targeted courses over a few days or weekends to address many of these issues.

5. The Crisis when Exiting the Company

Exiting a company requires a value driven transaction between a willing seller and a willing buyer at a price that creates a win-win for both parties.

This is easier said than done if the sale (or even transfer of assets to the next generation) takes place at an inopportune moment or after a traumatic event (usually involving the death/incapacity of a founding member) and/or when the SME is at a disadvantage.

The good SME owners of big or small enterprises understand that any exit from their company should be on their terms and therefore take the time to prepare for that eventuality.

For the exit plan to be effective the SME needs to position itself in a way that makes the firm’s ability to create shareholder wealth and value clearly visible.

Put simply the SME should (at any time) be in the enviable position where other players in the marketplace want to buy their company, but they do not want to sell. Unfortunately for most SMEs the reverse is true.

Relative Valuations

It is useful at this point for SMEs unfamiliar with how companies are valued to understand the underlying process. Many SMEs are familiar with Relative Valuations based on (a) Revenue Multiples that compare the buy-sell value with operational revenues and benefits earned, and/or (b) Profit Multiples that compare the value obtained with some description of profit to obtain a multiple.

Revenue Multiples are usually signposts of value that are used in isolation for start-ups, or where the earnings or profits cannot be obtained in the short term.

Profit Multiples using EBIT or profit after tax or cash flows are used more commonly, particularly with going concerns.

Relative valuations are easily understood and tend to feature in the buy-sell calculus of most SMEs. Where the process is based on the fundamentals of the business they are well done.

Good valuation brokers tend to average out the Earnings Valuation or the Free Cash Flows (see explanation below) of a number of businesses in a particular industry sector to arrive at a spread of low to high profit multiples at which a willing buyer or seller might negotiate a price.

On the other hand a number of brokers (and businesses for that matter) value a business on the spread of multiples based on the experience of the valuer (such as it is), rather than on the actual performance of the company. Where this happens good companies are often undervalued and lesser performing companies overvalued.

Since the value is arrived at between a supposedly willing buyer and a willing seller, SMEs see this overpaid goodwill as a costly lesson learnt. The loss is chalked up to experience and written-off over time.

The applicability of relative valuations for the acquisition of shares when a minority shareholder leaves the firm introduces a number of hooks in the valuation process.

Firstly, a minority shareholder exiting the company would have had a lesser part to play in the creation of value.

The risk is exacerbated in the case of minority shareholders who are also employees or directors and who elect to leave and work in the same industry, and possibly in direct or indirect competition with the SME. They take with them the strategic and working knowledge of the company and its client base, and force it to find replacement managers/directors at short notice.

Using multiples based on industry standards unconnected to business fundamentals in all such cases overvalues the company and disadvantages the remaining shareholders.

Good SMEs on the other hand recognise that it is the fundamentals of the business that should arguably drive value. They understand the need for visibility in value creation.

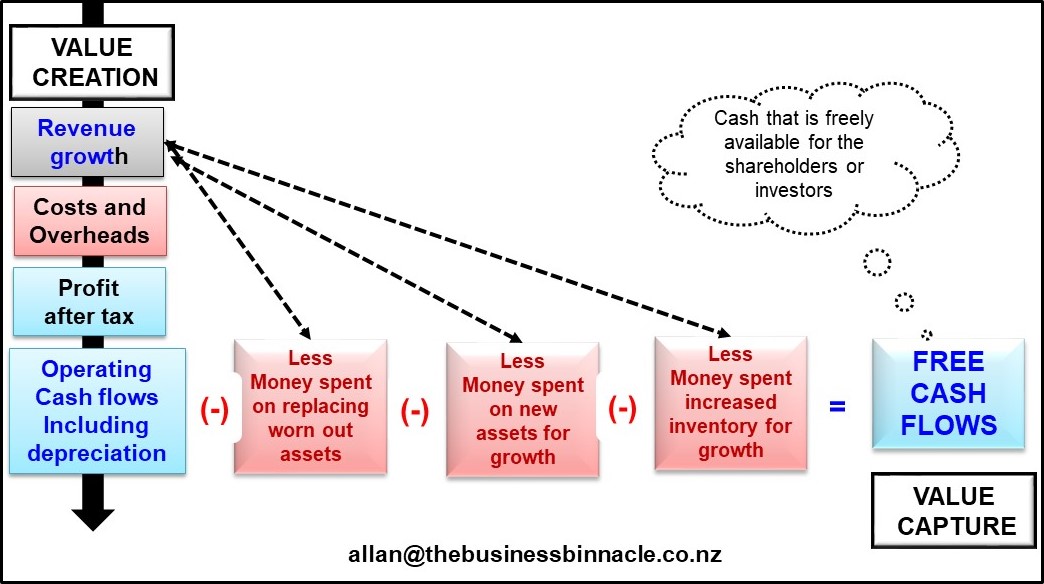

Managing a visible process from value creation to value capture/distribution is critical. Fundamentally this requires SMEs to understand the concept of Free Cash Flow that drives wealth creation…

The value of any company is the value over the long term (or horizon) of the current and future Free Cash Flows of the company.

The diagram clearly demonstrates that it is not profitability but the ability to translate profit into ‘real cash’ for the shareholders over the long haul that matters.

The profit (after tax) of the company is accordingly reduced to cater for the need to replace its worn out assets, the incremental fixed assets (Capex) and incremental investment in inventory needed to support and sustain growth.

The Free Cash Flows are what remains. They are cash returns that are freely available to the shareholders to reinvest or take away as dividends or drawings.

Any strategy that can increase revenues without increasing the need for additional assets or inventory increases the Free Cash Flows. This is the epiphany that good SMEs experience along the way.

The ability to generate and sustain Free Cash Flows over the long horizon drives the business fundamentals underlying any valuation model.

Without overcomplicating this paper with the underlying formulae of the discounting method for valuation (which is actually quite easy to use and understand), a typical SME (of any size) should have some understanding on how to manage their company by managing its value. A non-technical approach to managing value is described below.

Non-technical approach to valuing earnings (Free Cash Flows) of SMEs…

The basic concept is driven by a very simple construct. If the value of the company is in its ability to deliver Free Cash Flows in perpetuity (for as long as one can), common sense says that any action by the SME to grow these cash flows will add value.

Conversely if these cash flows are to be sustained (perpetuated year upon year) then the risks inherent in the long and short term should be addressed.

There are two levels of management that play into this logic.

At the management (operational) level the company should be both profitable and efficient. This value element requires a focus on the product-service value proposition and competitive advantage, good internal processes that are aligned with the customer value offered, and supported by the right people with the right mix of motivation and skills to deliver on that customer promise.

Most SMEs are good at this. The great ones actually excel at this level.

At the governance level there is a need to look at the true cost of the company in terms of its need for assets and liabilities to support its strategies. The focus here is on how to manage the business model in a way that maximises the Free Cash Flows:

- Growth is a critical factor, but it is not Revenue growth or Profitability growth alone that matters. What matters is the ability of the company to translate its revenues and profits into Free Cash Flows that are visibly available to its shareholders. That is the blood and guts of it all.

- Conversely any event (or any action) that jeopardises these cash flows devalues the company at an equal rate of knots. The higher the risk of the SME not delivering on these Free Cash Flows year upon year, the lower is the value of the company.

- For growing SMEs the higher the risk the higher will be the return demanded by equity investors (particularly from those who are outside the immediate family of investors). In simple valuation terms the value of these Free Cash Flows will be reduced by an amount commensurate with the high return demanded by its investors. Unfortunately this is done year upon year in a process called discounting, ergo “The higher the risk the higher the return demanded, the more the SME is penalised in terms of value.”

- The value of the firm obtained is then compared with its revenues or its profits and converted into a spread of Revenue and Profit (EBIT) multiples that most SMEs are familiar with.

Whilst most SMEs are unable to deal with the complexities of the calculation they should be able to address the twin requirements of increasing the Fixed Cash Flows and mitigating any risks that would negatively impact on the ability of the firm to sustain these cash flows.

Graphing the free cash flows of the firm year upon year is a simple way of managing value.

SMEs with closed processes and/or with opaque systems find themselves at the bottom end of the value spread of multiples. SMEs with clearly visible value drivers find themselves negotiating the price they want.

Many SMEs apply all sorts of rules of thumb when buying or selling their businesses without understanding the underlying logic that drives these values. The fact that a particular sector provides a spread of multiples does not necessarily mean that an SME will actually attract those multiples, or be able to position itself at the top end of its value spread.

The reverse is also true, often tragically. A number of SMEs buy companies based on these perceptions of industry multiples without actually analytically looking at the fundamentals of the business at the level of its current and future Free Cash Flows.

As long as the business is profitable and revenues apparent there’s a “she’ll be right” approach that often penalises neophytes who buy a small company, only to discover they have grossly overpaid for its assets.

The better the visibility in value capture, the better the ability of the shareholders to make intelligent decisions on how much money to extract from the company, and how much to leave behind.

SMEs signal their value to the market in a mating dance that must be seen for what it is. The peacock with the finest feathers and the largest strut attracts the best mate. Future buyers will clearly be very enamoured with investing in a company whose value capture processes are clearly on display.

SMEs seeking an exit should begin planning for their departure and tidying up the various ‘hotspots’ that will impact adversely on them years before the event. The sooner the value capture process is aligned with the business, the easier it is to sell the business at its true potential.

The departure of a shareholder is always traumatic. Each type of exit presents a different ‘unique risk’ profile to the remaining shareholders of the firm.

The unfortunate death or incapacitation of a shareholder is the least risky, provided the surviving trust beneficiaries do not automatically have a right to a seat on the board, which can be problematic as well. Assuming the firm retains the option to buy out the shares of the deceased or incapacitated shareholder at any time, they present a lesser benign risk.

There is then a case to be made for a payout that recognises the value created by the shareholder/director in the past and on his or her hand in positioning the firm for the future.

Conversely, shares being compulsorily acquired from a defaulting shareholder, or even from those shareholders choosing to leave and perhaps work for (or start up) another company present a high risk to the remaining shareholders. They take with them a significant part of the intellectual capital and working knowledge of the firm that restrictions of trade rarely manage to prevent (if at all).

Either of these typical examples mentioned above require the risks inherent in such scenarios to be recognised and the shares valued accordingly.

A concurrent issue is the timing and conditions for a payout. Since the shares are closely held and any essential funding to meet the working capital and growth of the firm are organically met from within the resources of the company, there is likely to be little in the way of cash flows available for a payout even in the most deserving of cases.

There is also a need to protect the firm from shareholders seeking a payout (or cash out) at their convenience, or if they find better returns from investments elsewhere.

They may even engineer a situation that requires their shares to be compulsorily acquired to the detriment of the remaining shareholders.

There are also genuine cases where shareholders will need to exit the firm as they grow older. This is likely to happen at some stage when there is an age gap between the legacy shareholders (founders of the SME) and the newer shareholders who may have recently joined.

It is useful for the shareholders to recognise the need for, and arguably even plan for, an exit policy but it must be understood that any planned succession is a difficult and often elongated process. Deciding which parts (if any) should be included immediately in the shareholders agreement, and which parts should be left for later, is critical, so that the signing of the shareholders agreement document is not inordinately delayed.

Conclusions

Successful SMEs tend to be creative, innovative, and flexible enough to reinvent themselves and even turn on a dime in a heartbeat. Kiwis tend to punch well above their weight in a number of business sectors. Many of their stories are legendary.

It is unfortunate however that only a select few of these SMEs actually achieve their true potential, partly because they themselves are often unaware of how much more they can achieve, but mostly because there is little understanding or appetite for attracting resources from outside their comfort zone.

For many SMEs these problems lie in their too-hard basket amongst things that “they would do, if they could do; but they can’t”.

This paper seeks to capture in some small way the endless possibilities that might come their way if they chose to look outside their wheelhouses every once in a while.

For those SMEs who have created the many great companies in New Zealand and have no wish to grow any further, transitioning to a new generation of owners and/or gracefully exiting the company with a fair share of the value they have created is critical.

Hopefully this paper (at the very least) opens their eyes to the endless number of possibilities that might be.

References

Bibliography and references freely available and well known in the marketplace and/or from peer reviewed sources form the underlying logic of this paper.